When I first left my marriage, I was used to being shouted at every day and being subject to violence every now and again. I thought I had become desensitised to conflict and aggression, but of course, as soon as it stopped and I began to recover, I became hypersensitive. The sound of people shouting gave me flashbacks or sent me into a panic attack and I became paranoid that other people were angry with me. I found myself in the strange position of being able to cope with fairly extreme violence in films, but falling apart when a character punched, slapped, pushed or even yelled at another character in a domestic context.

Around this time, I noticed the amount of domestic violence used for comic effect in movies. It generally goes like this

Male character is trying to get on with his adventure. This is either a comedy or an action film that doesn't take itself too seriously, so his adventure has some ludicrous elements (although it will all turn out well in the end). Female character – wife, girlfriend, occasionally mother – identifies his behaviour as ludicrous and becomes upset. They argue, he says all the wrong things and she ends up slapping him, hitting him with something, kicking him in the goolies etc.. He goes on his way and continues his adventure, intending to make it up to her – or win her back if she's told him to go to hell – when his mission is accomplished.It's funny because the protagonist is a tough guy who is going to bring down some really bad guys and she's just a woman. A staple of comedy is when someone we perceive as vulnerable (e.g. a mouse, a little old lady, a small boy left home alone at Christmas) attacks and defeats someone we had hitherto perceived as invincible (e.g. a cat, a trained assassin, a pair of hardened burglars). This is why it is funny for our tough hero, loveable as he is, to be humiliated and assaulted by a woman. And it doesn't matter. Women's violence is so utterly inconsequential that it is actually funny.

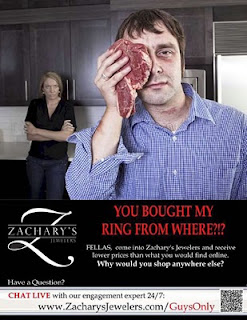

This advert is from the US and originally appeared here (since removed). Hat tip to Ami Angelwings.

This advert is from the US and originally appeared here (since removed). Hat tip to Ami Angelwings.Image Description: A poster-style ad dominated by a picture of a white couple. In the foreground, a man in his thirties holds a steak up to one side of his face. There is bruising beneath the other and another bruise or possibly a birthmark on his neck. In the background, a woman stands with her arms crossed, scowling at him. Below the picture reads in capital letters, “You bought my ring from where?!” in large red letters. In a smaller typeface there proceeds an advert for “Zachary's Jewelers” and in particular an invitation to chat to their engagement ring expert.

Personally, I think it is an appallingly ineffective advert. Your average man who is anxious about buying an engagement ring will likely be in the throws of tremendous romantic feeling, anxious above all things to please a person who he believes to be thoroughly lovely, maybe even anxious about whether they'll say “Yes”. He's thinking romantic thoughts and his greatest fear will be their disappointment or rejection. At such a stage in his life, a joke about his true love being a status-obsessed thug is not going to go down well. I worry for them both if it does.

Any man who is genuinely anxious about buying the right engagement ring (or anything) out of fear of assault needs quite another kind of helpline. After he's phoned the police. And given up on the idea of getting engaged to this lady or indeed seeing her ever again.

Oh sorry, what am I thinking? Women's violence is so utterly inconsequential that it is funny. Ha ha ha! And the joke is on her. Because everyone knows that women are insatiable materialists! And the engagement ring is a big status symbol; all their female friends will see it and she wants them to admire it and ask where it came from. So of course she'd be upset if it came out of a Christmas cracker. And the poster merely exaggerates this concern about her upset for comic effect. We sympathise with the bloke, but he should know what women are like! And it's only a black eye. Men are made of tougher stuff than to care about that. After all, they'd have no problem defending themselves if they really needed to.

I have had many black eyes. I don't know what the normal quota is, but I seemed to get a lot as a child. First one I ran into a drainpipe (like you do), I got another from a football when I miscalculated a header (like I always did), I got quite a few from toppling over and then as an adult, I gave myself one by bashing my head against a bedside table in my sleep. A black eye is no biggy. But I've been assaulted in ways that didn't bruise at all and that's a different kettle of stinking rotten fish.

It's not about being injured and whether you can cope with pain, bruising or whatever. When someone assaults you, it is scary. When someone who says they love you, who you trust and live with assaults you, there are ways in which it is even scarier. There's a sense that if this can happen – that a loving person can do the opposite of a loving thing - anything can happen, nothing is safe. If someone assaulted you on the street, you would attempt to defend yourself or run away, but having a soul and what have you, you can't hit the person you love and there are myriad reasons why you don't want to run away, ranging from fear through to pity, with love and loyalty in between. There's also the sense that if the person who loves you the most, who you think is great and good and super, if this person can be driven to act in such a way and says it's because you're so useless and stupid and irritating, then you're pretty much the crappest thing there is. And that's how abuse works, whether there's violence involved or no. And there's nothing magic about being a man which makes you invulnerable to that.

And I say it's not about being injured, but even in the UK, where we're very unlikely to see an advert joking about this (I think and hope), a man is murdered by a partner or ex-partner once every three weeks. Being a big strong man can be advantageous in physical confrontation, but like they say in the gangster films, it's sometimes more about how far a person is prepared to go. If someone is prepared to assault you, especially if you're someone they claim to love, they are seriously scary. Most people aren't prepared to assault anybody outside hypotheticals.

The advert just made me feel sick. I don't get full blown panic attacks any more. I think it made me feel just as a sick as it would have done if it had been an injured woman. Women are more vulnerable to domestic violence, there are cultural and economic reasons for this and women are more likely to be seriously injured or killed. But that doesn't make it necessarily better to be a male victim. You're less likely to be killed (though you're more likely to commit suicide). You're also less likely to recognise what is happening to you as abuse, you're less likely to seek help and you run far greater social risks in doing so.

I was thinking about this and the way that women's violence towards men can be joked about in ways that male-to-female violence cannot, when a t-shirt reminded me that it's just different.

This T-Shirt was available from the UK store Topman at the beginning of this week.

This T-Shirt was available from the UK store Topman at the beginning of this week.Image Description: A red t-shirt with black writing. It reads “I'm so sorry but...” above a list of excuses with empty tick-boxes beside them, as follows: “You provoked me, I was drunk, I was having a bad day, I hate you, I didn't mean it, I couldn't help it.”

There was a welcome fuss about this on Twitter and elsewhere on Wednesday and Topman quickly withdrew this and another t-shirt. Weirdly, the greater kerfuffle seemed to be about the other one, which was both odd and misogynistic in equal measure. It read, “Nice new Girlfriend. What breed is she?” It's like a cryptic crossword clue, the answer to which is Stay Away From This Man.

The t-shirt came to my notice on the same day of yet another report (contains a graphic image of facial injuries) about vulnerable teenagers being abused by their boyfriends and girlfriends, and about teenage girls in particular considering violence within their relationships to be normal. I imagine Topman were aiming at this kind of market – this vein of masculinity that says I'm an absolute arsehole and I don't mind who knows about it. Boys wear t-shirts that boast of their drunkenness and lechery, so why not hitting girls? It's a normal part of being a bloke. They tell the girls it's normal. They tell the girls it's normal with all the sentiments listed.

Both the advert and the t-shirt point to problems around masculinity – both are aimed at men, and fairly young men at that. One says it's funny if men get beaten up, the other says it's funny if men beat up women. We know that sexist humour cannot be divorced from sexist behaviour. And you know, in my experience, abusers tend to find their own behaviour fairly hilarious. Having your distress laughed at is part of the package of abuse. An abused man who sees the advert will already know that he should be subject to ridicule and an abusive man who sees that t-shirt will already know that his excuses are kind of funny. Both men have their ideas confirmed for them.

Ugh.

..............

Incidentally, I realise I am likely to have erased domestic violence within same gender couples in this, but I don't think the attitudes I'm discussing are applied equally to same gender couples (domestic violence in same gender couples tends to be ignored altogether). Certainly, I've never seen or heard any humour about same gender domestic violence. And whilst I am certain that gender is used as a weapon against all victims of domestic violence, even by abusers of the same gender, I don't think the kind of thing I'm talking about is relevant to those scenarios. I don't know. Please tell me more.

Incidentally, I realise I am likely to have erased domestic violence within same gender couples in this, but I don't think the attitudes I'm discussing are applied equally to same gender couples (domestic violence in same gender couples tends to be ignored altogether). Certainly, I've never seen or heard any humour about same gender domestic violence. And whilst I am certain that gender is used as a weapon against all victims of domestic violence, even by abusers of the same gender, I don't think the kind of thing I'm talking about is relevant to those scenarios. I don't know. Please tell me more.