I had read that you should try to write fiction

with just one particular reader in mind, even if your reader is an entirely imaginary

person. It’s a mistake, I read, to write for a broad audience. It’s easy, I

read (and found out for myself) to get distracted by the idea of different

people reading your work. You can’t please everyone. You may shock, annoy or

offend some of them. And you don’t want to write the book that wouldn't

shock, annoy or offend anyone at all.

Instead, I read, you should identify someone who you think

will really enjoy what you’re trying to do. If you don’t know anyone like this, invent them. Make them up and keep them in mind.

I didn't know anyone like that, so I made them up; my

imaginary ideal reader. Not someone who would unquestioningly adore every word

I wrote, but someone who would love what I wanted to achieve.

I made them up and kept them in my mind. They were quite appealing to me so they became

a secondary character in my novel, a love interest in a rather unromantic book.

I made them up. Then a friend sent me to their blog.

………..

My novel was near completion when 2010 came around. I had

worked so hard, for so long, with so many damn set-backs. There had been

periods of months where I couldn't write, because I was too sick or because all

my energy was otherwise spoken for.

There had been periods of months where I couldn't write because my

confidence had been comprehensively flattened. And now, finally, I was nearly

there.

|

| A satellite image of the UK in January 2010. |

This was a long, hard winter, the coldest in my life time. There

was snow about for weeks. My then husband had had an

argument with his family at Christmas and was spiraling into depression. In

January,

my friend Jack died suddenly – the third friend who, having enthused

about my writing and looking forward to my completed novel, had died before I

was done (I’m putting this in the context of my novel-writing; this was not my

first, second or third thought on hearing of Jack’s untimely death). This was

the year I would turn thirty and I started doing a

Project 365, taking a photograph every day.

There was something else going on. I would like to say

that a rational calculation was taking place, but it wasn't. I would like to

say that I was beginning to stand up for myself, but I wasn't. I often say, of this time,

that my marriage was falling apart, but I didn't know that. Not yet.

I was very

happy. I was not happy. I felt extraordinary well-loved; for much of my adult

life, I’d been lonely, believing I was little more than a convenience or a useful ear to my friends, but that had all changed. Despite pessimism from my

then husband (nobody

will turn up and I’ll have to pick up the pieces!), I was planning a thirtieth

birthday party with my three close friends. Two of them were old friends

by then, but I’d only recently realised what that meant.

And thus, I felt full of love, but a love like molten lead; I

was weighed down by it, burning up with it, in danger of starting a fire if I stood

too close to the curtains. Sometimes I basked in the warmth and light of it all. Other

times, I wanted to open a window and scream for help. That last sentence isn't

a metaphor.

The last two blog posts I wrote before I finished my novel were

On Not Being Beautiful #1 and

#2. These are strange to me now, because what I

wrote is perfectly valid, but I know they are written by someone who is regularly being

told that she has the face of a Klingon, the skin texture of a pizza, her arse takes up all three lanes of the motorway or some variation of the

above. At the same time, she has friends who casually tell her how good she

looks, who greet her “Hello gorgeous!” or sign off e-mails, “Keep smiling,

beautiful.” She's trying to navigate the dissonance.

Everything was rather like this. My friends were excited as I moved

towards the end of my book, while my then husband said I wasn't going to make

it and mocked every error or slur in my speech with, “I thought you were

supposed to be good with words.”

………………

During the last month of novel writing, I went a little mad and this madness was that bloody novel. It sounds dreadfully pretentious -

suffering for my art - and I do know it was completely unnecessary. If my life had been

better, it would have not made me sick and, crucially, my work could have improved. I didn't have to bleed all over the page (metaphor), I didn't have to

go into hell and back just to get the words down (not sure). These days I can

write with greater power and much less pain and mess. Back then, I was in pain. I was a mess.

|

This is the sort of thing I got up to at this time.

(A sort of pyramid made up of white blister

packs on top of a wall socket against a red

wall. A tiny metal angel looks on.) |

I couldn't work all day long, but it became very much harder to shut down my mind or escape into other things. I couldn't sleep when I tried and fell asleep with my

fingers on the keyboard. I lost interest in food. I was sometimes confused about whether I was living in the story of my life or the story I was writing.

I listened to music of flight and music of falling. I did a little yoga every day and always finished playing Otis Redding's cover of

(Can't get no) Satisfaction. I played the Cranberries’

No Need To Argue album an

awful lot, just as

the daffodils came into bloom.

Other things too, I would understand differently later on; my long exaggerated startle reflex was now ridiculous. Someone could casually approach me, no loud noise, no sudden movement and I would cry out in alarm. Then there were moments of high drama, threats and shouting where I noticed I felt nothing - worse, I was thinking about some trivial aspect of my novel, as if what was happening in the room was some unfathomable soap opera on the TV in the background.

I was also trying to help my then husband, because he was really very unwell. Every day I spend time looking for jokes or funny stories to provide a moment's relief. I rented movies I thought he'd like and watched every one by myself first, in case there was something that would upset or annoy him. At one point, I bought him smiley potato faces in a desperate childish attempt to put a smile on his face.

The night before I finished the novel, I told him that I was starting to panic about the deadline I had set. He responded, “I don’t care.”

The next moment, an e-mail from Stephen;

How It Ends by Devotchka. I began to

listen, thinking,

Oh god, this is long and I have no time, it’s got accordians in it and I’m going to have to say something polite about it! but then the piano

started. It was oddly perfect. I listened to it on repeat as I worked. In the

morning, I played it again four or five times until I got up the courage to send

the long rambling e-mail I’d been writing, complete with a 144,000 word file

attached.

In this e-mail, I tried to tactfully address the fact that Stephen might recognise himself in one of the characters, but he mustn't read anything into it. After all, Stephen has a different reason to walk with a stick and references Dawn of the Dead rather than Chopper Chicks in Zombie Town as an allegory for human endurance. The personalities may be identical, but I wrote all that before I knew him. I made him up! I don't want Stephen to think I am secretly in love with him or anything.

I couldn't say all that. So I wrote around it. At a great length.

..................

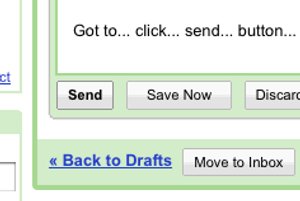

|

(The bottom of an unsent e-mail, reading

"Got to... click... send... button..") |

It is Sunday morning; Mother’s Day 2010. I take this screen grab

and put it on Flickr. Only one other person, apart from Stephen and I will see it and know what it means. But I am compelled to make some

public record.

Then I click send.

Everything has changed. I've written a novel. I am not the

same person I was yesterday, when I hadn't written a novel.

Stephen e-mails me with photographic evidence of my novel safely on his e-reader. He then sends the

Thomas Truax cover of I’m Deranged

in response to that weird rambling e-mail. Half

an hour later, he e-mails to tell me he’s read the first chapter. He's loving

it so far.

|

| (An e-reader held in a hand.) |

I haven’t mentioned the fact that I've finished my novel to

the man I am inexplicably still married to; I really hoped he would ask.

But I tell him that Stephen's read the first chapter. No congratulations. He says, “Sure he’s not on top of a

tall building, about to throw himself off to avoid reading the rest?”

My then husband is thinking about death a lot and imagines I have

the same effect on everyone.

It’s Mothers Day. I must spend time with my mother.

My parents and I go to my cousin’s house,

where we have a meal with two cousins and an aunt (we’re supposed to be eating

with my Granny, since it’s Mother’s Day, but we've managed to mislay her). We

catch up with what was happening with everyone’s life, apart from mine. We talk

about my sister, brother-in-law and nephew, we talk about other cousins, their

partners, aunts and uncles, we talk about Granny and the great uncles and

aunts. Even a couple of second cousins are mentioned at one point. Nobody asks

me a damn thing.

I notice this - I do notice it, from time to time, the way my

family believes I have absolutely no life to speak of - but I especially notice

today because I’m thinking,

This is the most important day of my life!

This really is. I consider blurting out, “I just

written my first novel!” but I don’t. And to be honest, it’s just good

to be out of the house and away from everything, to hear about other people's lives and dramas. People write books; it's not all that extraordinary. It's just extraordinary that I should.

It’s also good to have some time away from my laptop where I might anxiously await e-mails from Stephen. When I get back, he's e-mailing to complain that he had a sleep during the day and my book gave him nightmares.

The produce of my imagination has entered another person's subconscious.

…………

On the Monday, while Stephen is still reading my novel, my

then husband and I have a big talk. He tells me that he doesn't love me anymore. I am boring, unattractive and very difficult to live with. He knows he’s depressed and things may well change in time, so there's no point doing anything about it right now.

I have heard something like this before, several times. The routine is that I go on a sort of probation; try harder, avoid

pissing him off so much and after a while, I will say I love you and I’ll get

it back: “I love you too.”

But this time, I take it badly. A big chunk of the lovely

awful molten lead inside me breaks off, leaving a deep physical pain, a gaping

aching space in my chest where there should be no space. I weep. It is like

witnessing a death, the totality of loss I feel.

Yet, straight away, I feel lighter.

Lighter in a lost and listless way, but definitely lighter.

A friend and I have talked about me staying with her in Wales for a week sometime. I call her and we make a proper plan.

…………

On the Tuesday, Stephen finishes reading my novel. We talk

on Skype for about two hours. He loves it. He is brimming with praise and talk of the bits that scared, moved or amused him. He is so proud of me, he gets a little choked up saying so. There are issues with pacing. There are a shameful number of

typos. There are a few points of slight confusion. But he loves it.

When we've finished talking, the man who doesn't love me

anymore warns me, quite seriously, that I mustn't trust Stephen. He’s too nice.

He couldn't possibly be being honest about it.

I believe otherwise.