An A&E nurse friend described with despair the sharp increase in elderly people being admitted to the Casualty Ward around the third week of every December. At first I thought perhaps she meant that factors conspired in the same way that road accidents increase during the week after the clocks go forward - perhaps a combination of dropping temperature and old folk scrimping on heating in order to free up cash for Christmas. But no, she explained, at this time of the year, many people would attempt to get their elderly relatives put into hospital, so they would be out of the way over Christmas. In some cases, chronic conditions would become suddenly and mysteriously unmanageable. In some cases, there would be “falls” and other injuries.

Our cultural attitudes towards older people are fantastically bad, and this cannot be divorced from our attitudes towards disability. I've always felt that the temporary able-bodied as a way to describe non-disabled people is inaccurate on two counts – the first is the problem with the term able-bodied, the second is that many people will live out their lives without disability. However, if we live long enough, eventually everyone will be treated as if we are disabled. Older people are discriminated against because they are seen as the most useless, unattractive and burdensome disabled people of all, even when they have no impairments.

And whilst this is a terrible thing for elderly people, it effects all of us who have got more than a few years life expectancy. Disabled children lose status when they become adults. The ageism that has the media favouring the faces, voices and concerns of people in their twenties and thirties in general is even more profound for disabled people. If you google for images associated with Breast Cancer Awareness, you'd think that breast cancer was something that exclusively effected young white and conventionally beautiful women (and you might think that the point of the exercise was saving women's bosoms rather than saving lives). Breast Cancer is an important cause to many people because everyone knows someone who has or has had it, but four out of five of those people will be post-menopausal. Meanwhile, while we accept most younger disabled people are capable of an active life, sometimes physically, but if not then socially, perhaps academically or intellectually, an active retirement invariably means a non-disabled retirement. I think there are a number of factors here.

First off, older people cannot play the role of tragic hero when faced with impairment. There's the obvious and understandable fact that just as death is a different thing at ninety than it is at nineteen, a ninety year old has less to lose when she acquires an impairment than a teenager. A younger person loses more aspects of their future; a younger person who becomes disabled might miss out on educational or work opportunities, even the opportunity to have children, all of which will be behind the ninety year old. This is not to say that the losses of the ninety year old are not significant – and there are ways in which it might be worse. But I think it is understandable that we consider the loss of becoming disabled as less severe when someone is very old.

What is much less reasonable is that we regard severe levels of suffering and impairment in old age as inevitable. In fact, while many of us will acquire a collection of minor impairments and health problems as we grow old, a gradual miserable decline of physical health and mental faculty is relatively uncommon. Most of us will die of cancer, strokes or heart attacks – most of us will go relatively quickly (not that these three always guarantee a quick end, but they often do). Life expectancy in the UK stands at around 80, so in the last decade of an average lifetime, only one in twenty-five people will have dementia and about half will have arthritis (although there's arthritis and there's arthritis – for some people it is a constantly agonising condition, for others it is little more than an episodic increase in aches and creakiness).

Alongside dismissing the impairments of older people as inevitable, not proper conditions in themselves and therefore not deserving of disability status, we congratulate older people who are fortunate enough to be healthy and independent as if they have wilfully defied ill health in much the same way we congratulate younger disabled people as brave and heroic just for getting on with their lives. Meanwhile, young and middle aged people feel the stigma of old age associated with certain medical conditions (e.g. memory-loss, arthritis, incontinence) and especially with medical and adaptive equipment. When resisting equipment, people who have moved beyond the phase of “I don't want to feel disabled” often have a phase of “I don't want to feel like I'm old”.

I've already mentioned mobility scooters, and the way that it is okay to both laugh about them and propose that their use should be restricted because they are associated with doddery old biddies who run amok, knocking into pedestrians and leaving damaged street furniture in their wake. Young wounded war veterans who use wheelchairs or crutches are very likely to be involved in drinking culture, but it would be absolutely scandalous to joke about our brave boys being a danger to themselves and others and proposing that their mobility aids be confiscated until they sobered up. In fact, it's much more socially acceptable to joke about old people in general than it is to joke about disabled people, in a world where these categories are conceived as mutually exclusive.

Older disabled people just don't count for anything. Their practical difficulties count for less – criteria for disability benefits and social care for older people are massively more complex and limiting than for younger people. Their suffering is often dismissed altogether. We frequently see the phrase “older and disabled people” to refer to the group who use disabled access and facilities, when “disabled people” ought to do (if older people need these facilities, they too are disabled). I strongly believe that the potent cocktail of ageism and disablism makes older people suffer more and die sooner than they might otherwise.

My Gran had chronic debilitating depression for years and was dismissed as a miserable old woman (which she was and one preoccupied with her health, but that didn't mean she didn't need help). I realise that many younger people with chronic mental ill health struggle to get much more help than an anti-depressant prescription, but I've never heard of any older person getting any kind of talk therapy (outside exceptional projects that make the news or journals). In general, people get happier with every decade of maturity; people acquire the psychological equipment to cope with things, they gain a better perspective on life's troubles and often move to a position of simpler needs, hopes and fears. Yet for some reason, old age is seen as a naturally miserable time. Doctors and even family members declared that my Gran was just old, despite her considerable suffering and sometimes very bad behaviour towards others.

Now Gran has dementia. She's not depressed any more. She is sometimes very frightened, but sometimes she is more jovial than I have ever known her, giggling about silly things – even laughing at what she forgets. She doesn't know who most of us are and gets confused about her closest relationships, frequently treating her daughter like her mother. She often doesn't eat without encouragement, she struggles a great deal with her medication despite having an all bells-and-whistles doohicky that dispenses her pills on a timer and makes a noise to tell her when to take them. She has falls, but she is no longer able to think to press her personal alarm when she's in trouble. But the doctor reckons she's not any worse than she was two years ago when she was still keeping rough track of her sixteen grandchildren's birthdays (those memory tests are perhaps the most unscientific diagnostic tool currently used on the NHS). My Gran was not a very nice person, but now she is fantastically vulnerable and if it wasn't for the few family members she managed not to alienate during her depression, I don't know what would happen to her. Even if she is no longer quite her self, there is a person there who is a long way short of losing the capacity to suffer.

A lot of people kid themselves that people will naturally look after those more vulnerable than themselves. Very many people operate that way; very many people have a sense of responsibility towards those around them who have less capacity to take care of themselves. But this is something we've learned and as such, it is something that some people haven't learned. As long as older disabled people are invisible to the rest of the disability rights movement, a big group of us – including our future selves – will be subject to some of the worst abuse and social isolation, at a point in their lives when it can easily get too late to make things better.

But hey, here's a positive and quirky story about an older disabled person and his owls

Tuesday, September 27, 2011

Friday, September 16, 2011

Domestic Violence. Ha ha ha!

I haven't finished with the Disability Hierarchy, but this came up. In this post I'm going to show you a distressing image and discuss some distressing messages.

When I first left my marriage, I was used to being shouted at every day and being subject to violence every now and again. I thought I had become desensitised to conflict and aggression, but of course, as soon as it stopped and I began to recover, I became hypersensitive. The sound of people shouting gave me flashbacks or sent me into a panic attack and I became paranoid that other people were angry with me. I found myself in the strange position of being able to cope with fairly extreme violence in films, but falling apart when a character punched, slapped, pushed or even yelled at another character in a domestic context.

Around this time, I noticed the amount of domestic violence used for comic effect in movies. It generally goes like this

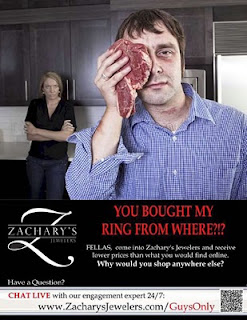

This advert is from the US and originally appeared here (since removed). Hat tip to Ami Angelwings.

This advert is from the US and originally appeared here (since removed). Hat tip to Ami Angelwings.

Image Description: A poster-style ad dominated by a picture of a white couple. In the foreground, a man in his thirties holds a steak up to one side of his face. There is bruising beneath the other and another bruise or possibly a birthmark on his neck. In the background, a woman stands with her arms crossed, scowling at him. Below the picture reads in capital letters, “You bought my ring from where?!” in large red letters. In a smaller typeface there proceeds an advert for “Zachary's Jewelers” and in particular an invitation to chat to their engagement ring expert.

Personally, I think it is an appallingly ineffective advert. Your average man who is anxious about buying an engagement ring will likely be in the throws of tremendous romantic feeling, anxious above all things to please a person who he believes to be thoroughly lovely, maybe even anxious about whether they'll say “Yes”. He's thinking romantic thoughts and his greatest fear will be their disappointment or rejection. At such a stage in his life, a joke about his true love being a status-obsessed thug is not going to go down well. I worry for them both if it does.

Any man who is genuinely anxious about buying the right engagement ring (or anything) out of fear of assault needs quite another kind of helpline. After he's phoned the police. And given up on the idea of getting engaged to this lady or indeed seeing her ever again.

Oh sorry, what am I thinking? Women's violence is so utterly inconsequential that it is funny. Ha ha ha! And the joke is on her. Because everyone knows that women are insatiable materialists! And the engagement ring is a big status symbol; all their female friends will see it and she wants them to admire it and ask where it came from. So of course she'd be upset if it came out of a Christmas cracker. And the poster merely exaggerates this concern about her upset for comic effect. We sympathise with the bloke, but he should know what women are like! And it's only a black eye. Men are made of tougher stuff than to care about that. After all, they'd have no problem defending themselves if they really needed to.

I have had many black eyes. I don't know what the normal quota is, but I seemed to get a lot as a child. First one I ran into a drainpipe (like you do), I got another from a football when I miscalculated a header (like I always did), I got quite a few from toppling over and then as an adult, I gave myself one by bashing my head against a bedside table in my sleep. A black eye is no biggy. But I've been assaulted in ways that didn't bruise at all and that's a different kettle of stinking rotten fish.

It's not about being injured and whether you can cope with pain, bruising or whatever. When someone assaults you, it is scary. When someone who says they love you, who you trust and live with assaults you, there are ways in which it is even scarier. There's a sense that if this can happen – that a loving person can do the opposite of a loving thing - anything can happen, nothing is safe. If someone assaulted you on the street, you would attempt to defend yourself or run away, but having a soul and what have you, you can't hit the person you love and there are myriad reasons why you don't want to run away, ranging from fear through to pity, with love and loyalty in between. There's also the sense that if the person who loves you the most, who you think is great and good and super, if this person can be driven to act in such a way and says it's because you're so useless and stupid and irritating, then you're pretty much the crappest thing there is. And that's how abuse works, whether there's violence involved or no. And there's nothing magic about being a man which makes you invulnerable to that.

And I say it's not about being injured, but even in the UK, where we're very unlikely to see an advert joking about this (I think and hope), a man is murdered by a partner or ex-partner once every three weeks. Being a big strong man can be advantageous in physical confrontation, but like they say in the gangster films, it's sometimes more about how far a person is prepared to go. If someone is prepared to assault you, especially if you're someone they claim to love, they are seriously scary. Most people aren't prepared to assault anybody outside hypotheticals.

The advert just made me feel sick. I don't get full blown panic attacks any more. I think it made me feel just as a sick as it would have done if it had been an injured woman. Women are more vulnerable to domestic violence, there are cultural and economic reasons for this and women are more likely to be seriously injured or killed. But that doesn't make it necessarily better to be a male victim. You're less likely to be killed (though you're more likely to commit suicide). You're also less likely to recognise what is happening to you as abuse, you're less likely to seek help and you run far greater social risks in doing so.

I was thinking about this and the way that women's violence towards men can be joked about in ways that male-to-female violence cannot, when a t-shirt reminded me that it's just different.

This T-Shirt was available from the UK store Topman at the beginning of this week.

This T-Shirt was available from the UK store Topman at the beginning of this week.

Image Description: A red t-shirt with black writing. It reads “I'm so sorry but...” above a list of excuses with empty tick-boxes beside them, as follows: “You provoked me, I was drunk, I was having a bad day, I hate you, I didn't mean it, I couldn't help it.”

There was a welcome fuss about this on Twitter and elsewhere on Wednesday and Topman quickly withdrew this and another t-shirt. Weirdly, the greater kerfuffle seemed to be about the other one, which was both odd and misogynistic in equal measure. It read, “Nice new Girlfriend. What breed is she?” It's like a cryptic crossword clue, the answer to which is Stay Away From This Man.

The t-shirt came to my notice on the same day of yet another report (contains a graphic image of facial injuries) about vulnerable teenagers being abused by their boyfriends and girlfriends, and about teenage girls in particular considering violence within their relationships to be normal. I imagine Topman were aiming at this kind of market – this vein of masculinity that says I'm an absolute arsehole and I don't mind who knows about it. Boys wear t-shirts that boast of their drunkenness and lechery, so why not hitting girls? It's a normal part of being a bloke. They tell the girls it's normal. They tell the girls it's normal with all the sentiments listed.

Both the advert and the t-shirt point to problems around masculinity – both are aimed at men, and fairly young men at that. One says it's funny if men get beaten up, the other says it's funny if men beat up women. We know that sexist humour cannot be divorced from sexist behaviour. And you know, in my experience, abusers tend to find their own behaviour fairly hilarious. Having your distress laughed at is part of the package of abuse. An abused man who sees the advert will already know that he should be subject to ridicule and an abusive man who sees that t-shirt will already know that his excuses are kind of funny. Both men have their ideas confirmed for them.

When I first left my marriage, I was used to being shouted at every day and being subject to violence every now and again. I thought I had become desensitised to conflict and aggression, but of course, as soon as it stopped and I began to recover, I became hypersensitive. The sound of people shouting gave me flashbacks or sent me into a panic attack and I became paranoid that other people were angry with me. I found myself in the strange position of being able to cope with fairly extreme violence in films, but falling apart when a character punched, slapped, pushed or even yelled at another character in a domestic context.

Around this time, I noticed the amount of domestic violence used for comic effect in movies. It generally goes like this

Male character is trying to get on with his adventure. This is either a comedy or an action film that doesn't take itself too seriously, so his adventure has some ludicrous elements (although it will all turn out well in the end). Female character – wife, girlfriend, occasionally mother – identifies his behaviour as ludicrous and becomes upset. They argue, he says all the wrong things and she ends up slapping him, hitting him with something, kicking him in the goolies etc.. He goes on his way and continues his adventure, intending to make it up to her – or win her back if she's told him to go to hell – when his mission is accomplished.It's funny because the protagonist is a tough guy who is going to bring down some really bad guys and she's just a woman. A staple of comedy is when someone we perceive as vulnerable (e.g. a mouse, a little old lady, a small boy left home alone at Christmas) attacks and defeats someone we had hitherto perceived as invincible (e.g. a cat, a trained assassin, a pair of hardened burglars). This is why it is funny for our tough hero, loveable as he is, to be humiliated and assaulted by a woman. And it doesn't matter. Women's violence is so utterly inconsequential that it is actually funny.

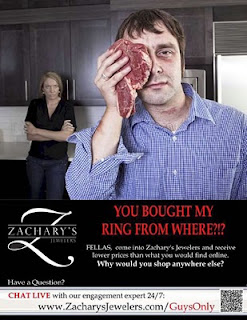

This advert is from the US and originally appeared here (since removed). Hat tip to Ami Angelwings.

This advert is from the US and originally appeared here (since removed). Hat tip to Ami Angelwings.Image Description: A poster-style ad dominated by a picture of a white couple. In the foreground, a man in his thirties holds a steak up to one side of his face. There is bruising beneath the other and another bruise or possibly a birthmark on his neck. In the background, a woman stands with her arms crossed, scowling at him. Below the picture reads in capital letters, “You bought my ring from where?!” in large red letters. In a smaller typeface there proceeds an advert for “Zachary's Jewelers” and in particular an invitation to chat to their engagement ring expert.

Personally, I think it is an appallingly ineffective advert. Your average man who is anxious about buying an engagement ring will likely be in the throws of tremendous romantic feeling, anxious above all things to please a person who he believes to be thoroughly lovely, maybe even anxious about whether they'll say “Yes”. He's thinking romantic thoughts and his greatest fear will be their disappointment or rejection. At such a stage in his life, a joke about his true love being a status-obsessed thug is not going to go down well. I worry for them both if it does.

Any man who is genuinely anxious about buying the right engagement ring (or anything) out of fear of assault needs quite another kind of helpline. After he's phoned the police. And given up on the idea of getting engaged to this lady or indeed seeing her ever again.

Oh sorry, what am I thinking? Women's violence is so utterly inconsequential that it is funny. Ha ha ha! And the joke is on her. Because everyone knows that women are insatiable materialists! And the engagement ring is a big status symbol; all their female friends will see it and she wants them to admire it and ask where it came from. So of course she'd be upset if it came out of a Christmas cracker. And the poster merely exaggerates this concern about her upset for comic effect. We sympathise with the bloke, but he should know what women are like! And it's only a black eye. Men are made of tougher stuff than to care about that. After all, they'd have no problem defending themselves if they really needed to.

I have had many black eyes. I don't know what the normal quota is, but I seemed to get a lot as a child. First one I ran into a drainpipe (like you do), I got another from a football when I miscalculated a header (like I always did), I got quite a few from toppling over and then as an adult, I gave myself one by bashing my head against a bedside table in my sleep. A black eye is no biggy. But I've been assaulted in ways that didn't bruise at all and that's a different kettle of stinking rotten fish.

It's not about being injured and whether you can cope with pain, bruising or whatever. When someone assaults you, it is scary. When someone who says they love you, who you trust and live with assaults you, there are ways in which it is even scarier. There's a sense that if this can happen – that a loving person can do the opposite of a loving thing - anything can happen, nothing is safe. If someone assaulted you on the street, you would attempt to defend yourself or run away, but having a soul and what have you, you can't hit the person you love and there are myriad reasons why you don't want to run away, ranging from fear through to pity, with love and loyalty in between. There's also the sense that if the person who loves you the most, who you think is great and good and super, if this person can be driven to act in such a way and says it's because you're so useless and stupid and irritating, then you're pretty much the crappest thing there is. And that's how abuse works, whether there's violence involved or no. And there's nothing magic about being a man which makes you invulnerable to that.

And I say it's not about being injured, but even in the UK, where we're very unlikely to see an advert joking about this (I think and hope), a man is murdered by a partner or ex-partner once every three weeks. Being a big strong man can be advantageous in physical confrontation, but like they say in the gangster films, it's sometimes more about how far a person is prepared to go. If someone is prepared to assault you, especially if you're someone they claim to love, they are seriously scary. Most people aren't prepared to assault anybody outside hypotheticals.

The advert just made me feel sick. I don't get full blown panic attacks any more. I think it made me feel just as a sick as it would have done if it had been an injured woman. Women are more vulnerable to domestic violence, there are cultural and economic reasons for this and women are more likely to be seriously injured or killed. But that doesn't make it necessarily better to be a male victim. You're less likely to be killed (though you're more likely to commit suicide). You're also less likely to recognise what is happening to you as abuse, you're less likely to seek help and you run far greater social risks in doing so.

I was thinking about this and the way that women's violence towards men can be joked about in ways that male-to-female violence cannot, when a t-shirt reminded me that it's just different.

This T-Shirt was available from the UK store Topman at the beginning of this week.

This T-Shirt was available from the UK store Topman at the beginning of this week.Image Description: A red t-shirt with black writing. It reads “I'm so sorry but...” above a list of excuses with empty tick-boxes beside them, as follows: “You provoked me, I was drunk, I was having a bad day, I hate you, I didn't mean it, I couldn't help it.”

There was a welcome fuss about this on Twitter and elsewhere on Wednesday and Topman quickly withdrew this and another t-shirt. Weirdly, the greater kerfuffle seemed to be about the other one, which was both odd and misogynistic in equal measure. It read, “Nice new Girlfriend. What breed is she?” It's like a cryptic crossword clue, the answer to which is Stay Away From This Man.

The t-shirt came to my notice on the same day of yet another report (contains a graphic image of facial injuries) about vulnerable teenagers being abused by their boyfriends and girlfriends, and about teenage girls in particular considering violence within their relationships to be normal. I imagine Topman were aiming at this kind of market – this vein of masculinity that says I'm an absolute arsehole and I don't mind who knows about it. Boys wear t-shirts that boast of their drunkenness and lechery, so why not hitting girls? It's a normal part of being a bloke. They tell the girls it's normal. They tell the girls it's normal with all the sentiments listed.

Both the advert and the t-shirt point to problems around masculinity – both are aimed at men, and fairly young men at that. One says it's funny if men get beaten up, the other says it's funny if men beat up women. We know that sexist humour cannot be divorced from sexist behaviour. And you know, in my experience, abusers tend to find their own behaviour fairly hilarious. Having your distress laughed at is part of the package of abuse. An abused man who sees the advert will already know that he should be subject to ridicule and an abusive man who sees that t-shirt will already know that his excuses are kind of funny. Both men have their ideas confirmed for them.

Ugh.

..............

Incidentally, I realise I am likely to have erased domestic violence within same gender couples in this, but I don't think the attitudes I'm discussing are applied equally to same gender couples (domestic violence in same gender couples tends to be ignored altogether). Certainly, I've never seen or heard any humour about same gender domestic violence. And whilst I am certain that gender is used as a weapon against all victims of domestic violence, even by abusers of the same gender, I don't think the kind of thing I'm talking about is relevant to those scenarios. I don't know. Please tell me more.

Incidentally, I realise I am likely to have erased domestic violence within same gender couples in this, but I don't think the attitudes I'm discussing are applied equally to same gender couples (domestic violence in same gender couples tends to be ignored altogether). Certainly, I've never seen or heard any humour about same gender domestic violence. And whilst I am certain that gender is used as a weapon against all victims of domestic violence, even by abusers of the same gender, I don't think the kind of thing I'm talking about is relevant to those scenarios. I don't know. Please tell me more.

Monday, September 12, 2011

The Disability Hierarchy 5: Wheel Life Drama

By far the most popular international symbol for disability is a wheelchair user. Proper disabled people are wheelchair-users. When anyone wants to represent disabled people pictorially, anywhere from government leaflets to children's books, they will invariably opt to draw or photograph a wheelchair-user.

By far the most popular international symbol for disability is a wheelchair user. Proper disabled people are wheelchair-users. When anyone wants to represent disabled people pictorially, anywhere from government leaflets to children's books, they will invariably opt to draw or photograph a wheelchair-user.Of course, the position of wheelchair-users in our society is a weird one, because quite obviously, you can't hide a wheelchair. You can't pass as non-disabled and as such, you get differential treatment wherever you go. However, your mobility impairment is recognised immediately. Many, if not all, of your accommodation needs are obvious and considered automatically legitimate. So what you lose in social privilege by never being mistaken for non-disabled, you partially regain in going straight to the top of the disability hierarchy, a phenomena that Sue has described as The Leg-tatorship (which I mostly enjoy because of the implication about who runs a dictatorship).

A proper wheelchair user, in the popular mind, is a paraplegic or double above the knee amputee, who has such high upper-body strength that he can make the chair jump up a staircase if there is no ramp. Some wheelchair symbols even incorporate this active image (I have recently seen even more active symbols, as if the wheelchair is taking flight, but I can't find them today). Some of the discussion about such symbols can be unintentionally alienating to people who are dependent on batteries or other people to get around, and of course ignores the matter that most disabled people are not wheelchair-users.

The vast majority of wheelchair-users in films and on television are paraplegics or double-amputees who self propel their wheelchairs – certainly all the heroic ones are. In real life, very few of us have lost total mobility in our legs. Usually, it's just that we can't walk far enough to make it worthwhile, because of pain, fatigue, weakness, spasticity, poor co-ordination, stiffness or a combination of the above. In other words, there aren't many wheelchair-users who have straight-forward impairments which start and stop with the inability to walk (not that even paraplegia is quite so simple). Many of us don't use a wheelchair around our homes.

So there is a massive but entirely artificial division between walking and wheeling. I imagine most people who have become wheelchair-users through chronic illness will have experienced both their own and others anxieties about early wheelchair-use, as if it's a huge negative step. The narrative where someone struggles on, resisting further tokens of disability before finally succumbing to wheelchair-use (or asking for help, claiming benefits, whatever) is an appealing and popular narrative within the Tragedy Model of Disability, but it is also genuinely tragic that a helpful piece of equipment carries such enormous psychological weight.

In the same way, many of us have experienced the vast difference in social attitudes and accommodation between walking with mobility impairments and wheeling. Like I say, you become very definitely disabled, that brings a load of nonsense with it and there is less room for compromise around physical access. But as a younger ambulant woman, strangers would sometimes consider it okay to challenge my need to stop, sit down, take a taxi, use a disabled loo because they couldn't see any impairment (although principally, because they were rude people). On the subject of disabled parking, non-disabled people and even some full-time wheelchair-users often seem to have the idea that if you can walk at all, you have no mobility impairment. In reality, painful walking requires far more time, planning and a greater reliance on disabled facilities in order to get around. In the wheelchair, I'm sat down, so it doesn't really matter if I have to take the long way round.

Margo has written about how others have regarded her ability to shuffle about inside the house as a sign that her condition is relatively mild compared to full-time wheelchair-users, despite the many severe functional impairments she has. I fully concur. My physical impairments get in the way of many things, but the pain that causes them is infinitely more difficult to manage. And much worse still is the cognitive impairment which stops me working, being able to drive, being able to socialise, being able to look after myself and being able to do very much outside the house without help. I would ask my fairy godmother for improvements in many different aspects of my health before we got onto making me walk better and further.

However, there is an increasing attitude that this is the twenty-first century, the world is now fully accessible (did you notice? I must have slept through it!) and being a wheelchair-user is not a big deal. The new Personal Independence Payment which is going to replace Disability Living Allowance is based on this premise; if you can self-propel a wheelchair, then your mobility impairment incurs no more cost than if you were fully ambulant. Lisa has written about what a disaster that will be, and Sassy Activist has written about the massive unseen cost of being a wheelchair user.

And naturally, there is a hierarchy of wheels! I'd like to have written a hierarchy of all mobility aids, but I'm not confident of the difference in social attitudes towards crutches, walking frames and so on. I know there are differences – for example, I know people who use crutches all the time are often asked what they have done to themselves, because crutches are seen as temporary. I know that walking frames are associated with old age and all the stigma that entails. I perceive that it is far more acceptable, even now, for men to have walking sticks or canes, presumably because of their history as a masculine fashion accessory.

And so to

The Hierarchy of Wheels

Assistant wheelchair – bottom rung of the wheelie ladder. When I am pushed in a manual wheelchair, far fewer people interact with me. It is as if your (assumed or actual) inability to self-propel suggests an inability to communicate. Sometimes, I do struggle to communicate, but that doesn't mean I'm not present. Of course, with an assistant wheelchair, people are provided with a convenient ambulant person who is always with you and who they can address over your head.

So there are times when being in an assistant wheelchair is much like being a ghost. Many people don't merely ignore you, but behave as if they can't see you, as if they don't want to see you. A smaller group of people simply stare, but don't interact with you – never smile back if you smile at them. I really don't know what I'd be without those sensitive perceptive people who feel that ghosts are people too.

Assistant-wheelchairs are extremely rare in film and on television, except to depict total incapacity – e.g. McMurphy arrives back on the ward in One Flew Over The Cuckoo's Nest in an assistant wheelchair having been lobotomised. Mr Pots from It's a Wonderful Life has an assistant wheelchair, but I think that's merely historic – if that film was remade today (God forbid!) he would definitely be a powerchair-user.

Scooter – For some reason, when I think of all the stories of disability street harassment from friends and acquaintances, scooter-users are over-represented. I've not used scooters a lot, but as a young not-fat woman, I think I'm in an advantageous position when I do. Mind you, in 2005, Ms Wheelchair of America was stripped of her crown because she used a scooter more often than a wheelchair. This lead to a lot of odd on-line discussion about wheelchairs, scooters, the ability to walk a few steps and one's qualification as disabled.

Scooter – For some reason, when I think of all the stories of disability street harassment from friends and acquaintances, scooter-users are over-represented. I've not used scooters a lot, but as a young not-fat woman, I think I'm in an advantageous position when I do. Mind you, in 2005, Ms Wheelchair of America was stripped of her crown because she used a scooter more often than a wheelchair. This lead to a lot of odd on-line discussion about wheelchairs, scooters, the ability to walk a few steps and one's qualification as disabled.

Scooters do seem to have a emasculating image which I don't understand. For one thing, it's often the only way you can off-road if you have bad legs. Little boys are often fascinated by mobility scooters – especially if they are being ridden by a grown up man. And perhaps more than any other disability tech, scooters have the potential for superhero conversions [links to The Sun]. Yet as a young man, Stephen has experienced so much street harassment as a scooter-user that it's become a routine experience.

Meanwhile, very overweight scooter-users are massively stigmatised with the idea that fatness vaccinates against all non-weight-related conditions (as mentioned here) and fat people must be using scooters out of laziness - something Renee has written about. (Personally, I don't know why people would be upset even if people did use scooters out of laziness – who exactly loses out by that?)

Older scooter-users on the other hand are considered a menace because old people are hilariously doddery and did you hear about the old biddy who ran her scooter into the canal? Ha ha ha! Older disabled people are going to get their own post in this series but suffice to say that older people themselves and anything associated with them – conditions, equipment and so on – sits very low on the disability hierarchy.

Scooter-users are immensely rare in films and on television. In fact, apart from the occasional mad-granny-on-a-scooter used for comic purposes, I can't think of a single example. Anyone?

Electric wheelchair / powerchair – things get a lot better. My most positive experiences of going out and belonging in the wider world on wheels have been with my electric wheelchair. A much higher proportion of strangers are able to look you in the eye and address you directly. Stephen Hawkins is a powerchair user and is perhaps the most famous disabled person on Earth.

Meanwhile, very overweight scooter-users are massively stigmatised with the idea that fatness vaccinates against all non-weight-related conditions (as mentioned here) and fat people must be using scooters out of laziness - something Renee has written about. (Personally, I don't know why people would be upset even if people did use scooters out of laziness – who exactly loses out by that?)

Older scooter-users on the other hand are considered a menace because old people are hilariously doddery and did you hear about the old biddy who ran her scooter into the canal? Ha ha ha! Older disabled people are going to get their own post in this series but suffice to say that older people themselves and anything associated with them – conditions, equipment and so on – sits very low on the disability hierarchy.

Scooter-users are immensely rare in films and on television. In fact, apart from the occasional mad-granny-on-a-scooter used for comic purposes, I can't think of a single example. Anyone?

Electric wheelchair / powerchair – things get a lot better. My most positive experiences of going out and belonging in the wider world on wheels have been with my electric wheelchair. A much higher proportion of strangers are able to look you in the eye and address you directly. Stephen Hawkins is a powerchair user and is perhaps the most famous disabled person on Earth.

Although powerchairs are relatively rare in film and fiction, wheelchair-using villains almost always use electric wheelchairs; Davros, John Lumic (who invents the Cybermen in a parallel universe), Rygel from Fascape, The Man with The Plan from Things to do in Denver when you're dead, Dr Loveless from The Wild Wild West eventually even Blofeld. It seems there's something sinister about moving about by the use of a joystick – like I say, if Mr Pots was around now, that miserly dude would be packing batteries. If it wasn't for Professor X and Odell Watkins in The Wire none of us would ever be trusted. Oh yeah, and Dominique Pinon's character in Alien 4, but I think he may be as ashamed of that role as I am to have seen the movie*.

Self-propelled wheelchair – top of the props! People who self-propel their wheelchairs can be entirely fit and healthy and sometimes very muscular and sporty. Some self-propelling wheelchair-users are so physically fit, sporty, successful and wealthy, they can happily call for the abolition of the word disability, because you know, it's such a negative word and they don't want to be thrown in with the rest of us who aren't nearly so brilliant (sorry, it's still fresh).

But as I've said, there is the increasing perception that anything is possible, workplaces, homes, transport and so on are now completely accessible, right? And whilst other disabled people may be looked at and presumed to be non-disabled, self-propelling wheelchair-users are increasingly looked at and presumed to have no more impairments than the one that can be seen. Not to be in pain, not to have difficulties caring for themselves or getting around. Our culture struggles with the idea of multiple impairments and possibly struggles even more when one impairment is very obvious and others are not.

However, self-propelling wheelchair-users have no shortage of positive famous role-models, in politics, sports and entertainment as well as no end of positive characters (if rarely central protagonists) in films and television drama; Ironside, Ron Kovic in Born on the Fourth of July, Dan Taylor in Forest Gump, Kenny in The Book Group, Adam Best in EastEnders, Josh Taylor in Neighbours, Joe Swanson in Family Guy and the highly controversial Artie in Glee.

And oh look, they're all men! And would be all white, except I've just remembered Stevie from Malcolm in the Middle. And then just as I was about to give up, Stephen pointed out that character played by the lovely Gina McKee in Notting Hill was a self-propelling wheelchair-user. Oh and I've just remembered Eileen Hayward in Twin Peaks. Well, that's all right then.

------------------

I hope you appreciate that when I list disabled characters from films, I'm sure there are others, probably far more obvious ones who have escaped my mind. So feel free to join in with my compulsive listing. One of these days I may create a blog post listing all disabled characters in films and television, as nobody seems to have tried to write a complete list yet.

* In fact, for all its faults, Alien 4 (or properly Alien: Resurrection) handles disability very well. The character is complete, both flawed and likeable in his own right and he just happens to use a (very cool) powerchair. The impairment is used but only as fairly minor plot points (e.g. he can't feel the Alien's acid blood when it falls on his leg, he uses the chair to smuggle contraband etc.) and never for the soaring pathos you can usually expect when you encounter a wheelchair-user in an action movie.

Thursday, September 01, 2011

The Disability Hierarchy 4: Diagnosis Matters

My cousin had a friend who was entering into his second heterosexual marriage. His first wife had died suddenly when they were both very young, and after her death he'd had an relationship with a man, in which he was physically and psychologically abused. The friend described himself as straight and said he had been taken sexual advantage of by his abuser at a point when he was deeply vulnerable. However, this chap's sexuality was a subject of immense speculation – and no small amount of amusement – between my cousin and her husband, other friends and enough of my own family for the story to get back to me. The general feeling was that this chap must be gay but pretending otherwise and his new marriage must be a sham. All manner of personal information and conjecture was sifted through, including a detailed discussion on what little interest this guy appeared to take in women's breasts.

A number of times in my life I have been privy to conversations among other white people where folk attempt to determine another person's ethnicity. It is a source of frustration and confusion when a person cannot be neatly categorised, as if, should it be impossible to generalise whereabouts a person's ancestors came from (let alone if someone has ancestors from more than one place!), it would be impossible to know how to treat them.

Marginalised people are at the mercy of privileged people in this way. People are allowed not to be straight, white, cis, non-disabled etc. but nobody is going to tolerate you unless they know which sort of substandard person they are so generously tolerating.

As disabled people, we are constantly expected to account for our status, by discussing our diagnosis, describing our medical histories and so on, even with strangers. Then we are compared to other people with the same diagnosis to make sure we fit into the popular perception of what a person with X condition is supposed to be like.

And thus one of the fundamental rules of the disability hierarchy is have a diagnosis. A few years ago, Wheelchair Dancer mentioned her diagnostic limbo – she has no overarching medical label which describes her impairments – and was responded to by rejection from other disabled people, who accused her of being a fraud (you know, that common scam of becoming a wheelchair-user just so you can dance as one). There are no medical mysteries! Either a doctor can tell you exactly what is wrong and why or else you're simply making it up.

But of course, there are plenty of medical mysteries, there is plenty of variation in the way conditions manifest and as such, lots of disabled people have long periods without a diagnosis. Other people have multiple diagnoses. Others have diagnoses which change over time. Others simply have rubbish diagnoses. For example, people who have agonising back pain which permanently impairs walking, sitting, standing etc. often lack diagnostic labels which differentiate between them and people who have temporary back problems that can be got over with rest and pacing. Chronic Fatigue Syndrome is an enormous umbrella under which which you have everything from persistent but manageable tiredness through to total paralysis and death. Mental illness criteria tend to be more specific but then our culture takes them and folk call themselves OCD for being overly tidy, or Bipolar when their mood changes suddenly.

In ten years time, there will be new labels for things people have now, and other labels will go away. Perhaps more than any other science, the terms used in medicine are constantly in flux as our bodies and pathologies are understood differently. Medical labels are utterly irrelevant to functional impairment. But they are even less relevant to who we are.

The second rule about diagnosis in the disability hierarchy is don't get a mental health diagnosis. It's a very common experience among people with chronic physical illness – especially but not exclusively women – to have our problems initially dismissed as “all in the mind” or dismissed with an actual mental health label. The problem here is the word dismissed. Because it doesn't matter how dramatic an illness is manifesting itself, the mere suggestion that it could be psychological means that it doesn't count. It is of your own making. It might as well be something that you chose to experience.

Misdiagnosis needn't be a massively traumatic experience. Let's take an imaginary person called Bonny who has Lupus. If she was misdiagnosed with MS for a while, then as long as they figured out the mistake before it became dangerous, then that really wouldn't be a problem. Conditions manifest themselves atypically. Details are missed. Accidents happen. Once I was told I had an inflamed hernia and it turned out to be constipation. I was relieved (eventually - ha ha ha! Sorry). If it had been the other way round I would have been anxious but not offended.

But say Bonny is misdiagnosed with depression. This ought not to be any kind of problem. A doctor taking all the information into account and proposing depression as a diagnosis ought not to be insulting. But the way Bonny is treated will be. This treatment may sometimes start with the doctors themselves, but if not family, friends, colleagues and employers will certainly oblige...

So, if that's what it is like for someone with a physical illness, how is it going to be for someone who does have chronic mental ill health? Their character is defamed all the same. Mental illness sometimes involves lapses in self-awareness and judgement, but it doesn't make a person chronically clueless as to how they are or what is happening to them. It doesn't render relapse and remission a matter of behaviour, willpower or the weather. And it doesn't change the nature of impairment dramatically. If depression or anxiety causes physical pain, that pain isn't going to be less dramatic than pain with a physical origin. On the contrary - it's likely to be harder to relax and play tricks on your mind to cope with it. If depression makes it impossible to motivate yourself to get out of bed, then you can no more get out of bed than if your limbs didn't work. Yes, the medical treatments for physical and mental conditions are very different, but our functional impairments are exactly the same.

This is the case even with hypochondria. A [cis male] friend of mine has hypochondria to such a degree that he once had to ask his GP for reassurance that he couldn't have cervical cancer, (to which the GP replied, “If you do, we're both going to be famous!”). But I have seen him when his mind has given him physical symptoms and it is a great cause of suffering and genuine impairment - even when he knows it's psychosomatic, he can't will the problem away. Instead he takes the necessary steps to recover in the same way that I respond to a crisis in my physical health. Some people don't know they have hypochondria, but convincing them that they do will not magic away the problem (and attempting to will probably increase their distress and with it their discomfort, and of course you could be wrong anyway).

One great irony is that the degree of doubt and mistrust towards people with mental health labels is exactly why some people do go into denial or lie about the nature of their illness.

A number of times in my life I have been privy to conversations among other white people where folk attempt to determine another person's ethnicity. It is a source of frustration and confusion when a person cannot be neatly categorised, as if, should it be impossible to generalise whereabouts a person's ancestors came from (let alone if someone has ancestors from more than one place!), it would be impossible to know how to treat them.

Marginalised people are at the mercy of privileged people in this way. People are allowed not to be straight, white, cis, non-disabled etc. but nobody is going to tolerate you unless they know which sort of substandard person they are so generously tolerating.

As disabled people, we are constantly expected to account for our status, by discussing our diagnosis, describing our medical histories and so on, even with strangers. Then we are compared to other people with the same diagnosis to make sure we fit into the popular perception of what a person with X condition is supposed to be like.

And thus one of the fundamental rules of the disability hierarchy is have a diagnosis. A few years ago, Wheelchair Dancer mentioned her diagnostic limbo – she has no overarching medical label which describes her impairments – and was responded to by rejection from other disabled people, who accused her of being a fraud (you know, that common scam of becoming a wheelchair-user just so you can dance as one). There are no medical mysteries! Either a doctor can tell you exactly what is wrong and why or else you're simply making it up.

But of course, there are plenty of medical mysteries, there is plenty of variation in the way conditions manifest and as such, lots of disabled people have long periods without a diagnosis. Other people have multiple diagnoses. Others have diagnoses which change over time. Others simply have rubbish diagnoses. For example, people who have agonising back pain which permanently impairs walking, sitting, standing etc. often lack diagnostic labels which differentiate between them and people who have temporary back problems that can be got over with rest and pacing. Chronic Fatigue Syndrome is an enormous umbrella under which which you have everything from persistent but manageable tiredness through to total paralysis and death. Mental illness criteria tend to be more specific but then our culture takes them and folk call themselves OCD for being overly tidy, or Bipolar when their mood changes suddenly.

In ten years time, there will be new labels for things people have now, and other labels will go away. Perhaps more than any other science, the terms used in medicine are constantly in flux as our bodies and pathologies are understood differently. Medical labels are utterly irrelevant to functional impairment. But they are even less relevant to who we are.

The second rule about diagnosis in the disability hierarchy is don't get a mental health diagnosis. It's a very common experience among people with chronic physical illness – especially but not exclusively women – to have our problems initially dismissed as “all in the mind” or dismissed with an actual mental health label. The problem here is the word dismissed. Because it doesn't matter how dramatic an illness is manifesting itself, the mere suggestion that it could be psychological means that it doesn't count. It is of your own making. It might as well be something that you chose to experience.

Misdiagnosis needn't be a massively traumatic experience. Let's take an imaginary person called Bonny who has Lupus. If she was misdiagnosed with MS for a while, then as long as they figured out the mistake before it became dangerous, then that really wouldn't be a problem. Conditions manifest themselves atypically. Details are missed. Accidents happen. Once I was told I had an inflamed hernia and it turned out to be constipation. I was relieved (eventually - ha ha ha! Sorry). If it had been the other way round I would have been anxious but not offended.

But say Bonny is misdiagnosed with depression. This ought not to be any kind of problem. A doctor taking all the information into account and proposing depression as a diagnosis ought not to be insulting. But the way Bonny is treated will be. This treatment may sometimes start with the doctors themselves, but if not family, friends, colleagues and employers will certainly oblige...

- If she raises the matter of symptoms that don't fit, then she is either imagining or lying about those symptoms.

- If she raises the fact she doesn't think she is depressed, then she is in denial or lying. She has no self-awareness.

- If her health doesn't improve, then she is resisting treatment, she is misbehaving and failing to pull herself together.

- If her health deteriorates dramatically, then she is seeking attention, or letting self-pity overcome her, or maybe it's because the weather is so bad this week.

- If she has a good day or a remission, then it will be believed to be because she is working out her problems, coming out of herself, or maybe it's because the sun is shining, etc..

So, if that's what it is like for someone with a physical illness, how is it going to be for someone who does have chronic mental ill health? Their character is defamed all the same. Mental illness sometimes involves lapses in self-awareness and judgement, but it doesn't make a person chronically clueless as to how they are or what is happening to them. It doesn't render relapse and remission a matter of behaviour, willpower or the weather. And it doesn't change the nature of impairment dramatically. If depression or anxiety causes physical pain, that pain isn't going to be less dramatic than pain with a physical origin. On the contrary - it's likely to be harder to relax and play tricks on your mind to cope with it. If depression makes it impossible to motivate yourself to get out of bed, then you can no more get out of bed than if your limbs didn't work. Yes, the medical treatments for physical and mental conditions are very different, but our functional impairments are exactly the same.

This is the case even with hypochondria. A [cis male] friend of mine has hypochondria to such a degree that he once had to ask his GP for reassurance that he couldn't have cervical cancer, (to which the GP replied, “If you do, we're both going to be famous!”). But I have seen him when his mind has given him physical symptoms and it is a great cause of suffering and genuine impairment - even when he knows it's psychosomatic, he can't will the problem away. Instead he takes the necessary steps to recover in the same way that I respond to a crisis in my physical health. Some people don't know they have hypochondria, but convincing them that they do will not magic away the problem (and attempting to will probably increase their distress and with it their discomfort, and of course you could be wrong anyway).

One great irony is that the degree of doubt and mistrust towards people with mental health labels is exactly why some people do go into denial or lie about the nature of their illness.

Which brings me onto faking and attention-seeking. It seems to be received wisdom that some people will fake impairments for social gain - that some people will do it for financial gain seems obvious, because if there is a scam to be had, someone will have a go. Being disabled is a social disadvantage, but many non-disabled people seem to think that the special treatment we receive is some kind of privilege and as such cast doubt on people whose impairments they don't understand. Much like my cousin and her friend's sexuality.

Ironically, it is people with lower status diagnoses, including mental health diagnoses who seem most vulnerable to the accusation. And yet, quite obviously, those people who are so desperate for attention and sympathy to feign impairment will invariably pipe for very high status diagnoses. I've known of more than one person who falsely claimed to have cancer in order to intensify a new relationship. The faux-paraplegic is not such an unrealistic staple of fiction, from Little Dorrit onwards, because paraplegics have a very high status, miminising the negative social consequences of disability (please don't think I mean it doesn't suck).

Although people with Body Identity Integrity Disorder may not be motivated by attention and sympathy (and they are disabled), they also desire much higher status impairments than the ones they have - usually amputation or paraplegia.

And yet, the lower you get down the disability hierarchy, the more doubt is cast over you being disabled at all. This applies to non-paralytic back injury, many chronic illnesses, especially mental illness, but also dyslexia, ADHD and other "learning impairments". This all comes back round to the Charity Model of Disability. There is no consideration about the logic of faking impairment in these ways. Instead, like some great stingy societal insurance firm, non-disabled people don't want to award the magnanimity of their tolerance to anyone if they can afford not to.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)